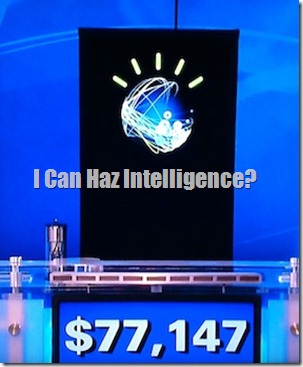

I was very impressed at how IBM’s creation Watson fared at Jeopardy. As a former computer scientist at places such as Google and Microsoft, I was actually more fascinated by Watson’s failures than its successes. Frankly, I was surprised that Watson didn’t answer every question correctly and faster than the humans. Watson missed obvious questions. To me, it seemed that the machine was great at trivia, the “fill in the blank” kind of questions. Things that any Google search can answer. But it failed at more complex problems, questions that involved things like metaphor and analogy, standard fare on SAT tests. It all led me to one conclusion:

We are still nowhere near achieving “artificial intelligence.”

Watson is just a machine, without emotion, drive, or ambition. I thought of a few questions I could easily ask it that it could never solve. “Who is standing to your left?” “How’s the lighting in here?” “Who does Ken Jennings remind you of?” “Fire! Please proceed to the nearest exit in an orderly manner.”

Yes, computer scientists have created something I call “programmed intelligence.” Intelligence in very specific domains, but as soon as you step outside the domain, the intelligence fails. Because “intelligence” isn’t just about recollection, computation, or pattern analysis. It’s much more about metaphor, symbolism, and relationships.

Think about a book for a moment. A book is really just a machine. It’s a Kindle with only one book available. The words are just dots of ink on the page that create letters. The letters form words, the words form sentences, paragraphs, and chapters. Computers can be made to understand how to display and edit those letters and words, even spot incorrect ones. But a computer can never read a book and understand what’s in it. It can look up every word and phrase, but never truly comprehend the meaning, the story. And even a book can never judge your emotion reaction to the story and respond accordingly. There’s as much intelligence in Watson as in any book on your bookshelf.

There were other subtle things that Watson failed to do on Jeopardy. He couldn’t learn from his mistakes (yes, computers can be programmed to learn, but that’s the equivalent of fixing a typo). It seemed that the other contestants learned and began to challenge the machine on the third day. More importantly, Watson has no idea why he made mistakes to begin with. Watson has no insight, no self-awareness. Imagine if Alex Trebeck had said “incorrect” to Watson on even correct, obvious answers:

“Answer is: The color of the White House. Watson.”

“What is white?”

“Incorrect. Ken?”

“What is white?”

“Correct.”

Watson would just hum along, completely oblivious. If Trebeck pulled that on Ken Jennings, he would storm off the stage or go after Trebeck’s throat.

So until we create a computer with emotion and true reasoning, we’ll never have intelligence, only super-fast trivia answerers.

So you’re wondering, “what does this have to do with my writing?”

The questions you should be asking yourself is, “How are my characters like Watson?” Do your characters react to their environment? Do they have their own agendas? Are they there just to provide other characters with information? Or are they living, reasoning creatures?

Another way to look at it is to ask, “What was at stake for Watson?” Yes, hundreds of computer scientists spent years on this project, but did Watson care? If there was indeed a fire alarm during taping, would Watson react? Do you think Watson really cared about how much money it earned? But every single character in your work cares about every interaction. There are stakes involved. They want something, and your other characters are either assistants or obstacles to those goals. Otherwise they are no better than the old books on your shelves.

So when you write your stories, keep one thing in mind: Don’t be a Watson.

NOTE: The writing content of this blog is moving soon! Check out the preview at The WriteRunner.

Great points. If I had to pick one thing in a book that bothers me the most, it's lifeless characters. A lifeless character had better be the guy who's already dead at the start of the murder mystery, and even then, I want to hear some interesting things about him throughout the book.

ReplyDeleteI want to be immersed in a book, I need to feel like I know the characters in order to care about them.

@Rebecca: LOL. Lifeless characters kill everything!

ReplyDelete