History

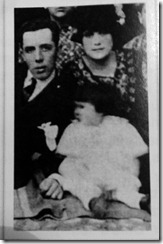

My great-grandfather Samuel Stumacher on the left, me on the right. Apparently goggles were not the rage back then.

I’m sitting here in a café, writing on my netbook computer. 110 years ago, my ancestors fled persecution using falsified documents with nothing more than the clothes on their backs. I know almost every American has a similar story in their background. But to see it come alive in one book was shocking to me.

Some of my ancestors are only known by their names, where they lived, and their approximate birth year. Many of the women have no maiden names known. These people are no more than lines in a census registry sitting in a government archive in Kiev, listed alongside their family members. So as a writer (and a human being) I start wondering about them. What did they do for a living? Did they love their spouses? What did they achieve that they are proud of? What are some of the challenges they faced? Did they have pets? How did they die?

A few of the lines in the census end with the word “conscripted.” These men were put in the army, and never heard from again. This was one of the “solutions” to the “Jewish Problem.” Cannon fodder. Back then, armies weren’t all comfy-cosy like they are today. It was virtual slavery which lasted 25 years before they were let go.

Women were all but ignored in the records. Daughters were married off and never heard from again. Wives seemingly came from nowhere. My thought was, “well someone must have a record of these people.” Yes. The synagogues did. Until they were burned. With their congregations inside. (I am not exaggerating this).

One of the most heart-wrenching mementos in the book is a letter written from a father to a son, begging for the son (a US WWI Vet who emigrated much earlier) to return from American and take them away. Why? Because pogroms were decimating the Jewish population. The father Nechamie literally did not know “hour-to-hour” whether he was going to stay alive.

Many people were killed, and our daughter Bassie had married, but her husband was murdered. Now she is left with a child, and has no means with which to keep it.

–Nechame Stumacher, 1920, translated

His son Barney did come and rescue them in an ordeal worthy of any Hollywood movie.

…56 extended family members set out in wagons for the Romanian border, They were robbed and harassed by soldiers but managed to get to the border…they were stopped by the police who noticed the [fake] passports sticking out of the neckline of Bassie’s dress (where she had hidden them)…

–Based on Barney Stumacher’s audiotape recollection

Pictured: Barney Stumacher, Bassie Stumacher, and the baby Blossom Batt, who incidentally lived to the age of 89 and died in 2009, survived by 4 children.

One thing that gets me is all the blank entries in the book…those people who stayed behind, those that didn’t “make it.” Their records continue up until 1939, then end. That is when the Nazis invaded the Ukraine. In the town where my ancestors are from, the Nazi’s executed 7,000 Jews. Seven Thousand. That was about a quarter of the town’s entire population. Two 9/11’s in one small town. I don’t know how many of my relatives died, but it’s probably dozens, if not hundreds. There were only a handful of survivors. The cousin who compiled this history did not consult the Holocaust records, and frankly I don’t blame him. It’s mortifyingly depressing.

There is one thing that gets me more than anything, one thing that I cannot shake, and maybe this is the part I can take into my writing. I think about the people that left, that came to America to start new lives. They left everything behind to sail into an unknown future, to travel to a land where they did not speak the language. You may think that they didn’t have much to lose given their circumstances, but I look at all my ancestors and see dozens that were born, lived, married, raised children, and died in that same town. Let me tell you something right now.

They did not want to leave.

I had a conversation with a friend of mine after 9/11 that I’ll never forget. The majority of people are simple folk. All they want is to have a chance for a happy life. To have a decent job, to marry someone they like, to raise a few kids. Nothing special. They want to build a home they live in the rest of their lives. Most of the people who died on 9/11 were just plain old office workers, janitors, moms and dads. And most of the people in Iraq, Iran, and Pakistan are exactly the same. People just want to live their lives.

I look at the records of my ancestors, and I see the same kind of people. Married, families, strong religious beliefs, and working simple jobs that kept food on the table. Shopkeepers, tailors, carriage drivers, carpenters. They did not want to leave. This was their home for generations. But then everything changed. Their homes were invaded. Their businesses were burned. Their husbands and wives were murdered, all tacitly approved by the government. They had no choice but to leave. Not all of them did.

I realized that these people were Heroes, in the truest sense of the word. They did the unthinkable. They moved their entire families to a strange country and faced countless dangers along the way. They faced death and survived (followers of my blog should see where this is going).

I’m not suggesting every story you write should be about people facing genocide, living in a dystopic hell. But if I could channel even a tiny portion of the emotion that I’m feeling right now about my ancestors, I think I will be a successful writer.

In your novel writing, consider whether your main character is truly facing an impossible choice, but in some ways, there should not be a choice at all. Your main character must do what they must do, face the enemy straight on, and risk everything. Only then can they be a Hero.

I can’t really think of many things more courageous or more difficult than what my ancestors achieved. If they had not found the means to leave, if they decided to “wait it out” or hope for better times, then I would not be here today living in relative comfort, and their lives would have ended in a horrific way.

So I salute the man pictured above, Samuel Stumacher, for bringing his family of 8 (including my paternal grandmother at age 7) to New York in 1901. He did not live long enough to see my father’s birth (his grandson), but I know he’s up there somewhere looking down on his dozens of descendants. Thank you, Samuel.

PS Apparently Sholom Aleichem, famous Yiddish writer, lived for a few years in this very same town. He is the author of the story that Fiddler on the Roof is based on, which depicts life in a town that neighbors my ancestors’ town at that same time period.

It's a sad thing that so many people don't even seem to care about their family histories. This experience you've relayed here will hopefully encourage more people to talk to the oldest members of their families, to write or otherwise record the stories of their lives and the memories they have of those no longer living.

ReplyDeleteMoney, comforts, and the like are nice, but ultimately this just shows that families are our most valuable asset.

Very interesting. I would love to see it if possible.

ReplyDeleteVery well written. Inspirational.

A very moving post Andrew. One of the reasons that I love geneology and historical fiction is because they enable us to see events from history, that are too massive to comprehend (like the Russian pogroms and the Nazi atrocities), from a more personal point of view. It is overwhelming to think of 7,000 people being slaughtered. It is moving when you hear the stories of a few of them. It is life-changing when those stories are your family. What a treasure your cousin has given you!

ReplyDelete@QT: I met a lot of people when we took trips to Florida, but as a kid, I was like, "ugh, old people."

ReplyDeleteNow I wish I had talked to them more.

@בערי: I still haven't gone through the whole thing myself! (it's over 400 pages!)

@Mary: I knew they "came over" in the early 1900's but I always figured it was like, "hey, check out America! Let's go!" and not a last-ditch effort to stay alive.

What a beautiful tribute to your family Andrew. I was very moved. I can't even imagine what they might have gone through. Thank you.

ReplyDeleteThank you for sharing that, Andy. Years ago I visited NYC, and took the ferry to see the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island. To me, Liberty was OK, but Ellis Island hit me right in the gut.

ReplyDeleteWhen you go into the museum, the first thing you see is a pile of luggage -- satchels, trunks, bags large and small -- that are actual pieces used by immigrants who came through Ellis Island. Then, in another section of the museum, there are exhibits of actual things families brought with them. Cooking pots and utensils, family Bibles, heirloom christening dresses, photographs.

All of that really made me stop and think, "What would *I* pack if I were leaving forever and going into the unknown?"

Andrew, thank you for sharing these stories about your family history. It's so moving to read about what they had to go through, the horrible struggles they faced. It's really amazing what they did and gave up to survive, and so sad to think of all those who did not.

ReplyDeleteAndrew - wonderful post about family history! Not sure if you or your readers realize there is an entire community of genealogy bloggers with over 1,500 blogs covering everything from Australian Aboriginal genealogy to Jewish genealogy and more!

ReplyDeletehttp://www.geneabloggers.com

@Anne: Problem is, I can imagine, which is why I'm considering writing about it.

ReplyDelete@mschile: Unfortunately, what little my ancestors took with them was stolen, so they literally arrived with the shirts on their backs.

@Liz: Thanks. It's hard to give it justice.

@genea: Thanks for the link. This is more of a writing blog; I don't usually dive into Genealogy.